|

|

Definitions: Juxtaposition is the film editing technique of combining of two or more shots to evoke an idea or state of mind. A montage can be a juxtaposition of two shots, but commonly refers to the juxtaposition of multiple shots to depict an event often in stretched or condensed time.

Kuleshov Experiment

Subjects were asked to describe the man’s state of mind in each close-up. In fact, Mosjoukin’s close-ups were the same shot and his face expressionless. Subjects nevertheless answered sadness for the juxtaposition with the dead girl, hunger for the juxtaposition with soup, and lust for the juxtaposition with the woman on the divan. Discovery of the “Kuleshov effect” would establish the POV (point of view) shot and reaction shot as essential elements of filmmaking. Not that the Kuleshov effect is limited to POV-reaction shot juxtaposition. For instance, the Kuleshov effect is often employed to create a visual euphemism for violence, e.g., in “Blood and Wine” (1996), we see Jason (Stephen Dorff) about to stab a beached shark, followed by a flock of seagulls taking flight. Pure Cinema Montage Director Alfred Hitchcock labeled the Kuleshov effect “pure cinema” and regarded it as one of three types of montages. His pure cinema consisted of three shots—close-up, POV, reaction (close-up). In an interview, Hitchcock offered the example of a close-up of a squinting old man juxtaposed to a shot of a woman with a baby juxtaposed to a close-up of the old man smiling. Result: the audience sees a kindly old man. Replace the shot of a girl and baby with one of a girl in a bikini, and the audience sees a dirty old man. The Montages of “Psycho” (1960)

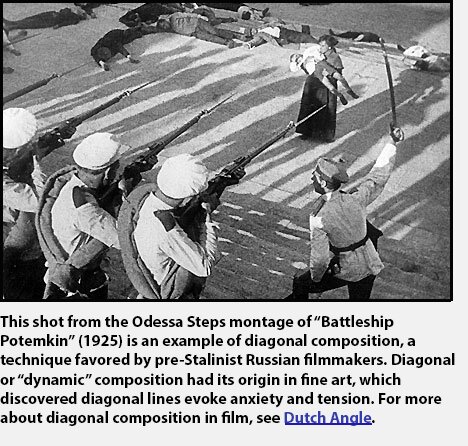

In the second “Psycho” montage, private detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is murdered. Hitchcock likened its composition to symphonic “orchestration” which begins with a waste shot of Abrogast slowly mounting the stairs, action likable to “violin tremolos.” Tremolos turn frenetic with a cut to an overhead shot of a woman rushing toward Abrogast with a raised knife. Cut to a close-up of Abrogast’s face being slashed by a knife, the equivalent of “brass.” Hitchcock’s creations were continuity montages, meaning that they primarily advanced the story rather than illustrate a concept, social condition, dream or state of mind. They were also in true time as opposed to montages that condense time (e.g., Jane (Katherine Heigl) modeling bridesmaid dresses for Kevin (James Marsden) in “27 Dresses” [2008]), or montages that stretch time (e.g., the slow motion shootout in the train station of “The Untouchables” [1987]). Credit the Russians Which returns us to Kuleshov and filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertovas, Russians who invented the art of montage during the Revolution. All were Bolshevik partisans who equated montage with truth and Hollywood continuity with bourgeoisie escapism. Techniques were many and included cuts from wide shots to extreme close-ups; transposed images and split screens; graphics, symbols and animations; extensions/condensations of space and time through slow motion, jump cuts, cuts between subjects and/or locales in coinciding time; and, with the coming of sound, movement synchronized with soundtrack. These techniques would not only be employed by Hitchcock and other Hollywood filmmakers, but became the foundation of music video editing known today as MTV-style editing.

Another seminal film is Vertovas’ “Man with a Movie Camera” (1929), a night-and-day documentary about Moscow that is simultaneously a celebration of Russian filmmaking techniques. In 2012, critics and directors voting in the international and prestigious Sight and Sound poll ranked “Man with a Movie Camera” history’s eighth greatest movie. Conducted every decade since 1952, the same poll ranked “Battleship Potemkin” in the top 10 every decade save 2012, when it was ranked first runner-up. |

History: The first filmmakers needed time to understand their new medium and realize the value of film editing. Most filmed action as if shooting a play or a sporting event. Cecil B. DeMille would be among the first filmmakers to recognize motion pictures are unique in the degree that they appeal to emotion. This emotional power DeMille tapped by being the first to regularly shoot close-ups of his actors. Moviegoers marveled at faces so large and attractive. From close-ups arose audience emotional attachments that transformed actors into movie stars. In 1911, the Hollywood fan magazines Photoplay and Motion Picture Magazine were first published and by 1916 their combined circulations approached a half million. “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces,” proclaims silent film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard” (1950).

History: The first filmmakers needed time to understand their new medium and realize the value of film editing. Most filmed action as if shooting a play or a sporting event. Cecil B. DeMille would be among the first filmmakers to recognize motion pictures are unique in the degree that they appeal to emotion. This emotional power DeMille tapped by being the first to regularly shoot close-ups of his actors. Moviegoers marveled at faces so large and attractive. From close-ups arose audience emotional attachments that transformed actors into movie stars. In 1911, the Hollywood fan magazines Photoplay and Motion Picture Magazine were first published and by 1916 their combined circulations approached a half million. “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces,” proclaims silent film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard” (1950).  Juxtaposition, film editing’s next major advancement, would make close-ups a staple of narration. The potential of juxtaposing close-ups with other shots would be objectively demonstrated in 1921 by a young Russian filmmaker named Lev Kuleshov. Subjects of the “Kuleshov Experiment” were shown a short film that included three close-ups of actor Ivan Mosjoukin followed each time by a different shot—a girl in a coffin, a bowl of soup, and a woman lying on a divan.

Juxtaposition, film editing’s next major advancement, would make close-ups a staple of narration. The potential of juxtaposing close-ups with other shots would be objectively demonstrated in 1921 by a young Russian filmmaker named Lev Kuleshov. Subjects of the “Kuleshov Experiment” were shown a short film that included three close-ups of actor Ivan Mosjoukin followed each time by a different shot—a girl in a coffin, a bowl of soup, and a woman lying on a divan.  Hitchcock cites two examples of different montages contained in his horror film “Psycho” 1960. The first is the famous scene in which Marion (Janet Leigh) is knifed to death in a shower. This montage consists of 78 shots that span 48 seconds. Hitchcock composed the montage partly to avert Production Code censorship of nudity and violence. But the scene is classic because of the artistic insight that made Hitchcock the “Master of Suspense”: an audience can be frightened more by what it imagines than what it sees.

Hitchcock cites two examples of different montages contained in his horror film “Psycho” 1960. The first is the famous scene in which Marion (Janet Leigh) is knifed to death in a shower. This montage consists of 78 shots that span 48 seconds. Hitchcock composed the montage partly to avert Production Code censorship of nudity and violence. But the scene is classic because of the artistic insight that made Hitchcock the “Master of Suspense”: an audience can be frightened more by what it imagines than what it sees.